Categorie - Categories

Amore

(13)

Bei libri da leggere

(12)

Cose belle - Beautiful things

(65)

Finnish for dummies - Finlandese per imbranati

(5)

Geopolitica per i miei studenti - Geopolitics for my students

(8)

I miei libri...Il mio romanzo.

(10)

Il mondo di Zenda

(2)

La mia cucina Ma cuisine

(83)

Manipulators and family abuses

(17)

Memories of school

(17)

My cinema

(43)

Poesie di Annarita

(90)

Roba di scuola

(18)

School memories

(10)

The spiritual corner

(47)

Visualizzazione post con etichetta I miei libri...Il mio romanzo.. Mostra tutti i post

Visualizzazione post con etichetta I miei libri...Il mio romanzo.. Mostra tutti i post

domenica 15 aprile 2018

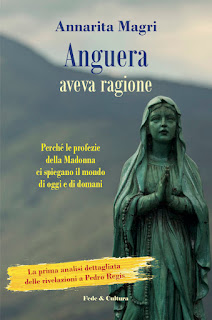

Il mio nuovo libro - Anguera aveva ragione

Il mio nuovo libro - Anguera aveva ragione

Cari Amici,

ecco qui il mio nuovo libro, pubblicato dall'editore Fede e Cultura, di Verona, nello scorso gennaio:

http://www.fedecultura.com/p/vetrina_30.html#!/Anguera-aveva-ragione/p/99766424/category=0

Questo libro è il frutto di 5 anni di ricerche e di un'analisi attenta e rigorosa dei messaggi che la Vergine darebbe, dal 29 settembre 1987, a un signore oggi di mezza età, allora diciottenne, Pedro Regis, ad Anguera, diocesi di Santana de Feira, presso Salvador Bahia in Brasile. Ho potuto incontrarlo più volte, parlare con lui e ne ho ricavato la convinzione che si tratti di una persona equilibrata. Inoltre, i messaggi contengono una vasta serie di appelli a costruire una vera e propria "civiltà dell'Amore" che l'Apparsa tratteggia con accenti accorati, perché ci vuole "felici in questa vita e nell'altra". Essi si mostrano del tutto fedeli alla dottrina cattolica e insistono sulla preghiera, l'amore vicendevole, la fedeltà alla Chiesa, la frequenza ai sacramenti, l'amore per gli ultimi e i poveri.

Col veggente, il sig.Pedro Regis

I messaggi superano ormai i 4.000 e comprendono anche un ricco insieme di profezie, probabilmente il corpus profetico più importante dell'ultimo secolo. Uno in particolare riprende il dettato del famoso Terzo Segreto di Fatima. Per studiarle, le ho raggruppate per argomenti, verificate nell'originale portoghese, analizzate e confrontate con i testi biblici, quindi con una ricca bibliografia di carattere geopolitico. Effettivamente, il quadro che ne esce è attendibile e compatibile con gli eventi di questi ultimi anni: sono profezie che si stanno progressivamente avverando. Il mio auspicio è che questo studio possa favorire l'evangelizzazione ed il lavoro della commissione istituita dal vescovo di Santana de Feira, mons. Zanoni Demettino Castro.

Chi fosse interessato all'acquisto può direttamente rivolgersi a me, oppure acquistare l'e-book o il cartaceo sul sito dell'editore al link sopra. Alcune copie sono disponibili anche alla cartoleria Mazzoni in via Pomposa a Ferrara e in altre librerie.

giovedì 23 giugno 2016

John's love (from my novel "The children of yesterday")

John's love

This passage, written by me on March 2014, concerns the love by John, the protagonist, for Ada (who is actually a little idealized). I dedicate it to my students, and to everyone who still believes in the "great love".

That morning, after a substantial

session of gymnastics in his cell - hundreds of push-ups, squats, sit-ups and

anything else - John made a kind of shower using the poor sink available, then

he lay on his bed, to read. But, that day, he could not focus. His mind was

repeatedly hooked by the thought of the hearing underway, hearing he was

interested in for various reasons. Inevitably, his thought slid to Ada and to

the admiration he nourished for her for all the effort and dedication she gave

evidence of. Well beyond many others. Equally inevitably memories cropped up

inducing him to compare her with other women he had met in his past.

When he was younger, John had never

needed to court a girl: they spontaneously ran after him, teenagers of his age

or a little less, and some even a few years older. The thing had even ended up

by almost boring him. His reserved nature, not exactly shy, but slightly

introverted and prone to isolate him, much more than it should seem from his

sudden outbursts of joy, didn't like the excessive favor some of them showed

him; moreover, his inherently sober, almost severe side couldn't tolerate any

coquetry. Of course, he had had numerous love stories and, not infrequently,

they had begun when he had answered to sweet glances from the girls of his age

he crossed: for one of them, when he was less than eighteen years old, he had

literally lost his head; but it was short-lived. Not that his feelings had

changed rapidly: it was her who had vanished when he had got, yet again, in

trouble. Who knows, perhaps discouraged by her parents, perhaps unconvinced

herself, perhaps frightened, she had never called him anymore: and he had

sought and waited for her in vain. It had happened a few years before he ended

up in the death row: and he had often thought of her in that period and later,

even when he went out with others or his feelings were petrified in the

death-row.

Yet, now he recognized that, even in the

most overwhelming passions, those so absolute of his early youth, he had always

kept an imperceptible, perennial shade of dissatisfaction; and it was

reverberated in that indefinable austerity he evaluated those same girls by.

Actually, the reason why, after all, he had trusted women so little when he was

free, was deeper. Over the years he had come to understand, or almost

understand it. What he didn't tolerate, when yet another girl with a pretty

face was maneuvering, not so covertly, to make his acquaintance at a party or

in a night-club, even when his male vanity was flattered and he responded

willingly, even when he ended the night in bed with one of them, it was the

superficiality he found in most of them. Involuntarily, John conformed to the

strict criteria absorbed in his family, while having constantly fought against

them. Deep down, he fed far more profound needs, perhaps even higher; and the

garrulous glee of several girls who ended up among his arms after a party, even

after both of them had been drinking, irritated him the next morning, when he

woke up with a headache next to one of them, full of bitter discontent. Not

infrequently, he also fed the impression that the girl on issue was

psychologically myopic and that her attention did not go far beyond his

attractive look. Virtually no one of those fleeting encounters had stood the

test of time.

With this severity not entirely

corresponding to him, John alternated doubts and guilt-feelings though.

Sometimes he regretted judging his former girl-friends too harshly and slid in

the belief that he was himself the main responsible of those emotional wrecks.

Sometimes he thought he had not understood what they needed and accused himself

of a kind of superficiality to be demonstrated. Ada preferred to speak of

weakness and depression: but he did not know whether he could trust the

magnanimity of that judgment, in his opinion directed by love. He forgot, in

those moments of self-criticism, that love lives of truth.

Then he had arrived on the death row.

The first years, he had received letters from some young women fascinated by

him after seeing him on TV or in the newspaper. The media had started to call

him "cold eyes" and perversely played on the contrast between his

almost angelic appearance, and the brutality of the crime he was accused of

and, with no way out, found guilty. Despite the bad description which was

offered about him, besides a completely unrealistic one, or maybe tickled just

by it, those there had fallen in love with him: and some had written to

him, without hesitating to reveal their attraction, an attraction not supported

at all by the knowledge of his personality. He had thrown away those papers

angrily. Even more than before, when he was used to perceive the interest he

aroused among girls while walking through a crowded room, he felt strongly that

those silly women didn't seek him, they didn't want him. In their

exaggerated sentences he felt, the falsity of an ephemeral and merely external interest.

He felt the burden of flattery. Then he preferred to be alone.

The only, true one he had courted and,

despite his reserve, doggedly courted, was Ada. His Ada. With her it had been

different since the beginning: at first friendship, then understanding, then

complicity blossomed, when she had not even seen him yet. What had captivated

him at once? The tone of her first letter? The sweetness by which she wrote to

him, the smiling understanding she showed him? Her cheerfully crazy humor, by

which she revealed she talked by herself all the time, addressing the most

unlikely interlocutors, including her soft toys? The care by which she was

concerned about his condition and recommended to him that he drank plenty of

water or ate as healthy as possible? Or her qualities?

Hell, what kind of woman Ada was! Able

to cross the world to come and visit him, to leave her country, her continent,

her career, her life to be with him: and then, with such an intelligence!

Acute, analytical, implacable: she had torn his case into pieces as perhaps

only he had managed. And she was convinced, rationally convinced that he was

innocent. Working with her was a genuine pleasure, priceless, because they were

complementary: she was analytical and rational, he more concise and intuitive.

But he was also attracted by the force of her will, a irony will, unsuspected

behind such a sweet face. In her work, she could put in place not completely

malleable individuals too.

And finally, looking at her was one of

the greatest pleasures of his life, second only to holding her among his arms:

John, who had always had a soft spot for brunettes, had collapsed already

seeing her first photos, back in the distant autumn 1998; but then, finding her

in front of himself, during their first visit, a year and a half later, for a

long time he had struggled with himself to not express his feelings at once. He

remembered he followed her with his eyes, so graceful and smiling, so sweet and

nice, without losing sight of her for a moment. He had seen her blushing

repeatedly under the fire of his eyes and, suddenly, when he had whispered

something ... Ah! Yup:

- You're much more beautiful than in a

photography - her cheeks were suffused with an adorable blush and then she had

slightly diverted her look towards the window. That moment had stayed inside

him ever since; and, then, he had contemplated her like this, a little

sideways, her eyes slightly lowered for a lovely, rare modesty, and he had been

tempted to declare her his love there, immediately, at once. Then, he realized

she could be embarrassed and he could make her feel uncomfortable: and, for the

umpteenth time, he had withheld his feelings. Eventually, though, the next day,

he had not been able to anymore.

For her he had totally put himself into

play, he had spent himself, he had bent backwards out of creativity. He had

never desired a woman so much as her, and not only because he loved her since

years and since years he could't almost touch her, being in the death-row: he

was perfectly aware that, if he had met her before, if only he had met her

before, he would have done anything for her.

Once he jokingly whispered to her:

- After all, I'm like those

sanctimonious daredevils who sow their wild oats for years and then they're

those who require the most serious girls; and they appear even the most

demanding. - He might have joked, but he told the truth. His relationship with

Ada was the highest fulfillment he had reached in his life. Nothing held the

comparison.

Meeting Ada meant to return to a

completely different conception of love: familiar to him, because not very far

from what he had heard from his parents, but different from what he, as a

rebel, had experienced since his adolescence. He had been living among

teenagers and young people in the late 80s, early 90s, used, in good faith, to

be carried away by relationships and to not control them too much, sure it went

okay like that.

Ada however, belonged to another world:

that of good girls and good boys who still wait for their first wedding night

to give themselves to their love. With her, he had learned the true meaning of

a value considered by the most out of date, almost an antique or a wreck

inducing discomfort: purity. Ada was sexy, according to him terribly sexy: she

radiated a sunny sensuality, limpid, worth the most exuberant summer days in

the Mediterranean land. She was like he imagined Italy: full of sun, colors,

human warmth. Her heart overflew with passion, a compelling, gentle, yet

intense passion, able to nourish not one, but one thousand one nights. Yet,

beside her, he breathed air of purity. Once she had explained him what she

meant by that word:

- Many think of purity as something

neurotic, full of fear, as if it consisted of a sum of external and artificial

prohibitions; and as if keeping it coincided with avoiding dirt stains, like

clothes to be put in the washing machine. But purity is more, much,

extraordinarily more than something so petty. Purity means harmony, means

primarily selflessness; it means true dedication, it means respect.

Here, for the first time in many years, with Ada, John had learnt on his skin the light caress of respect, a modest veil covering gently the loved person, the ecstasy of beig loved for the person he was. There was no need for her to tell him, because he was sure about that: she would never agree to end up sleeping with him after a party. And not that she did not wish for it: no woman, his manly instinct suggested to him, had desired him so much as her. During their visits together, her loving look was sliding on his features caressing them tenderly, it slid along his broad shoulders, arms, chest and his whole, tall figure with the sweet rapture of someone contemplating a wonder and who would never leave it. With her, John had understood, in its deepest meaning, why her demeanor would be so different; if she had known him outside, the true, only, great reason to wait for the supreme joy of a night among his arms, would be only one: her love for him.

A few lines of comment to this passage. I can say that its ground comes from true life; anyway, Ada's love is founded in something which can be very well expressed by the poem beneath.

so that you're not alone anymore.

I'm ready to give you what you need -

- esteem, comprehension, tenderness - and so much more.

I'm ready to adorn a fire-place with you -

and to make your house home.

I'm ready to share your plans and projects -

and to make them progress towards the horizon tiny line.

I'm ready to leave my country and to love yours as my own.

I'm ready to love your dear ones as if they were mine -

- for their own sake and because in them I'd see a spark of you.

I'm ready to heal your wounds, to feel your pain as my own -

- but also, to make you smile and laugh, to let you hope.

I'm ready to share with you the burden of passing years -

- to find a meaning in what is lost, and what we'll never have.

I'm ready to forgive you - and to need your forgiveness.

A woman should be the Paradise of a man - if she is just willing to.

Happyness knocks only once at the door - and now, she is at yours.

Opening to her requires prudence -

- but also the unavoidable crazyness of courage.

Immense is the regret coming from fear:

years of pain, afterwards, never end.

Life is heavy when, only when one says "no" to Love:

the true one, always coming from above.

Here, for the first time in many years, with Ada, John had learnt on his skin the light caress of respect, a modest veil covering gently the loved person, the ecstasy of beig loved for the person he was. There was no need for her to tell him, because he was sure about that: she would never agree to end up sleeping with him after a party. And not that she did not wish for it: no woman, his manly instinct suggested to him, had desired him so much as her. During their visits together, her loving look was sliding on his features caressing them tenderly, it slid along his broad shoulders, arms, chest and his whole, tall figure with the sweet rapture of someone contemplating a wonder and who would never leave it. With her, John had understood, in its deepest meaning, why her demeanor would be so different; if she had known him outside, the true, only, great reason to wait for the supreme joy of a night among his arms, would be only one: her love for him.

A few lines of comment to this passage. I can say that its ground comes from true life; anyway, Ada's love is founded in something which can be very well expressed by the poem beneath.

I remember one film by

K.Kieslowski, Decalogue

1, where the protagonist, a scientist who

has completely forgotten the supernatural side of our life, sees his computer

suddenly going crazy: and, on the screen, there is just a sentence: "I'm

ready". It is very suggestive and recalling the absolute. The absolute is

ready at our door ("I stand at the door, and I knock") with his love; but this love can be also

embodied in the love by a woman: a true woman. True love shows true Love:

that's what Ada's love says to John.

I'm ready

I'm ready to love

you - forever.

I'm ready to support

you and to stay by your side:so that you're not alone anymore.

I'm ready to give you what you need -

- esteem, comprehension, tenderness - and so much more.

I'm ready to adorn a fire-place with you -

and to make your house home.

I'm ready to share your plans and projects -

and to make them progress towards the horizon tiny line.

I'm ready to leave my country and to love yours as my own.

I'm ready to love your dear ones as if they were mine -

- for their own sake and because in them I'd see a spark of you.

I'm ready to heal your wounds, to feel your pain as my own -

- but also, to make you smile and laugh, to let you hope.

I'm ready to share with you the burden of passing years -

- to find a meaning in what is lost, and what we'll never have.

I'm ready to forgive you - and to need your forgiveness.

A woman should be the Paradise of a man - if she is just willing to.

Happyness knocks only once at the door - and now, she is at yours.

Opening to her requires prudence -

- but also the unavoidable crazyness of courage.

Immense is the regret coming from fear:

years of pain, afterwards, never end.

Life is heavy when, only when one says "no" to Love:

the true one, always coming from above.

L'amore di John (dal mio romanzo "I bimbi di ieri")

L'amore di John

Questo brano, che ritengo piuttosto poetico, risale al marzo 2014 e parla dell'amore di John, il protagonista del mio romanzo "I bimbi di ieri", per Ada (che, avverto, è un po' idealizzata). Lo dedico ai miei studenti e a chiunque sognasse ancora il "grande amore".

Quella mattina, dopo una consistente sessione di ginnastica in cella - centinaia di

flessioni, push-ups, squats, addominali

e quant'altro - John aveva fatto una specie di doccia servendosi del misero

lavandino a disposizione, quindi si era sdraiato sul letto, a leggere. Ma, quel

giorno, non riusciva a concentrarsi. La mente veniva ripetutamente agganciata

dal pensiero dell'udienza in corso, udienza cui si sentiva interessato per vari

motivi. Inevitabilmente, il pensiero scivolava su Ada e sull'ammirazione da lui

nutrita nei suoi confronti per tutto l'impegno e l'abnegazione di cui ella dava

prova. Ben al di là di tanti altri. Altrettanto inevitabilmente, affioravano

dei ricordi che inducevano in lui il confronto con altre donne da lui

incontrate in passato.

Quando

era più giovane, John non aveva mai avuto bisogno di corteggiare una ragazza:

gli correvano dietro da sole, adolescenti della sua età o poco meno, e anche

qualcuna di qualche anno maggiore. La cosa aveva finito addirittura quasi per

annoiarlo. Il suo carattere riservato, non propriamente timido, ma leggermente

introverso e tendente a isolarsi, molto più di quanto paresse dai suoi

improvvisi scoppi di allegria, non amava le manifestazioni di favore eccessivo

che certune gli dimostravano; per di più, il suo lato intrinsecamente sobrio,

quasi severo, non tollerava le civetterie. Certo, aveva avuto varie storie e,

non di rado, esse avevano avuto inizio quando lui stesso aveva risposto alle

occhiate dolci delle coetanee che incrociava: per una, quando era poco meno che

diciottenne, aveva perso letteralmente la testa; ma era durata poco. Non che i

suoi sentimenti fossero mutati rapidamente: era lei che si era dileguata,

quando lui si era cacciato, per l'ennesima volta, nei guai. Chissà, forse

dissuasa dai suoi, forse poco convinta ella stessa, forse impaurita, non si era

fatta più sentire: e lui l'aveva cercata e attesa invano. Era successo qualche

anno prima che finisse nel braccio della morte: e spesso vi aveva ripensato in

quel periodo e dopo, anche quando usciva con delle altre o i suoi sentimenti

erano rimasti impietriti nel death-row.

Eppure,

ora lo riconosceva, anche nel bel mezzo degl'innamoramenti più travolgenti,

quelli così totalizzanti della prima giovinezza, in lui era rimasta sempre

un'impercettibile, perenne sfumatura di insoddisfazione; ed essa si riverberava

in quell'indefinibile austerità con cui valutava quelle stesse ragazze. A dire

il vero, il motivo per cui si era, in fin dei conti, fidato abbastanza poco

delle donne quando era libero, era più profondo. Nel corso degli anni era

giunto a comprenderlo, o quasi. Quello che non tollerava, quando l'ennesima

ragazza dal bel viso manovrava, neanche tanto velatamente, per fare la sua

conoscenza a una festa o in un night, anche

quando la sua vanità maschile ne rimaneva adulata e lui rispondeva di buon

grado, anche quando finiva la serata a letto con una di esse, era la

superficialità che lui avvertiva nella maggioranza di loro. Involontariamente,

John si adeguava ai criteri severi assorbiti in famiglia, pur avendo

perennemente lottato contro di essi. Sotto sotto, nutriva esigenze ben più profonde,

forse anche più elevate; e la garrula gaiezza di varie ragazze che gli finivano

tra le braccia dopo un party, magari

dopo che avevano bevuto tutti e due, lo irritava la mattina dopo, quando si

svegliava col mal di testa accanto a una di loro, pieno di un'amara

scontentezza. Non di rado, nutriva altresì l'impressione che la ragazza in

questione fosse psicologicamente miope e che la sua attenzione non andasse

molto al di là dell'attrattiva costituita dal suo aspetto. Praticamente nessuno

di quegl'incontri fugaci aveva retto alla prova del tempo.

A

questa severità non del tutto sua, John alternava però dubbi e sensi di colpa.

Talora si rammaricava di giudicare le sue ex

in modo troppo rigido e scivolava nella convinzione di essere lui stesso il

maggiore responsabile di quei naufragi affettivi. Talora riteneva di non aver

capito di cosa loro stesse avessero bisogno e si accusava di una superficialità

tutta da dimostrare. Ada preferiva parlare di debolezza e depressione: ma lui

non sapeva se fidarsi della magnanimità di quel giudizio, a suo avviso

orientato dall'amore. Dimenticava, in quei momenti di autocritica, che l'amore

vive di verità.

Poi

era arrivato nel braccio della morte. I primi anni, aveva ricevuto delle

lettere di alcune giovani donne rimaste affascinate dopo averlo visto in TV o

sul giornale. I media avevano preso l'abitudine di definirlo "occhi di

ghiaccio": e giocavano perversamente sul contrasto tra il suo aspetto,

quasi angelico, e l'efferatezza del delitto di cui era accusato e, senza via di

scampo, ritenuto colpevole. Nonostante la pessima descrizione che di lui era

stata offerta, d'altronde una descrizione del tutto irrealistica, o forse

solleticate proprio per questo, quelle là

si erano invaghite di lui: e alcune gli avevano scritto, senza farsi remore a

rivelargli la loro attrazione, un'attrazione per nulla sostenuta dalla

conoscenza della sua personalità. Aveva gettato quei fogli con rabbia. Ancora

più di prima, quando era abituato a percepire l'interesse che suscitava nelle

ragazze nel passare attraverso una sala affollata, aveva provato la netta

sensazione che quelle sceme non

cercassero lui, che non volessero lui. Aveva avvertito, nelle loro frasi

esagerate, la falsità di un interesse effimero e meramente esteriore. Aveva

avvertito il peso dell'adulazione. Aveva allora preferito rimanere solo.

L'unica,

vera che avesse corteggiato e, nonostante la propria riservatezza,

accanitamente, era Ada. La sua Ada. Con lei era stato diverso fin dall'inizio:

era sbocciata prima l'amicizia, poi l'intesa, la complicità, quando lei non lo

aveva neancora mai visto. Cos'era stato ad avvincerlo da subito? Il tono della

prima lettera? La dolcezza con cui lei gli scriveva, la sorridente comprensione

che gli dimostrava? Il suo humour allegramente

pazzerello, con cui lei gli rivelava che parlava da sola di continuo,

servendosi degl'interlocutori più improbabili, peluches compresi? La cura con cui si preoccupava delle sue

condizioni e gli raccomandava di bere molta acqua o di mangiare il più sano

possibile? Oppure le sue qualità?

Miseria,

che donna era Ada! Capace di attraversare il mondo per venire a visitarlo, di

lasciare il suo paese, il suo continente, la sua carriera, la sua vita per

stare con lui: e poi con un'intelligenza! Acuta, analitica, implacabile: aveva

fatto a pezzi il suo caso come forse solo lui era riuscito. E si era convinta,

razionalmente convinta, che lui fosse innocente. Lavorare con lei era un

piacere genuino, impagabile, anche perché erano complementari: analitica e razionale

lei, più sintetico e intuitivo lui. Ma di lei lo attirava anche la forza di

volontà: una volontà di ferro, insospettabile dietro un viso tanto dolce. Nel

suo lavoro, riusciva a mettere a posto anche soggetti non del tutto malleabili.

E,

infine, guardarla era uno dei piaceri più grandi della sua vita, secondo solo a

tenerla tra le braccia: John, che aveva sempre avuto un debole per le brune,

era crollato già al vederne la prima foto, nel lontano autunno 1998; ma poi, al

trovarsela davanti durante la prima visita, un anno e mezzo dopo, aveva lottato

con se stesso a lungo per non manifestare i propri sentimenti subito. Si

ricordava che la seguiva con gli occhi, così aggraziata e sorridente, così

dolce e simpatica, senza perderla di vista un attimo. L'aveva vista arrossire

più volte sotto il fuoco del proprio sguardo e, a un tratto, quando lui le

aveva mormorato qualcosa...Ah! Sì:

-

Sei molto più bella che in fotografia - le guance le si erano soffuse di un

rossore adorabile e lieve e poi lei aveva distolto un poco lo sguardo in

direzione della finestra. Quel momento gli era rimasto dentro da allora; e,

allora, l'aveva contemplata così, un poco di profilo, lo sguardo leggermente

abbassato per un'incantevole, rara ritrosia e gli era venuta la tentazione di dichiararle

il suo amore lì, subito, senz'altro. Poi, si era reso conto che lei poteva

provare imbarazzo e che avrebbe potuto metterla a disagio: e, per l'ennesima

volta, si era trattenuto. Alla fine, però, il giorno dopo, non c'era riuscito

più.

Per

lei si era messo in gioco totalmente, si era speso, aveva operato acrobazie di

creatività. Non aveva mai desiderato una donna tanto quanto lei e non solo

perché l'amava da anni e da anni non poteva quasi toccarla, stando nel death-row: lui era perfettamente consapevole

del fatto che, se l'avesse incontrata prima, se solo l'avesse incontrata prima, avrebbe fatto di tutto per

averla.

Una

volta le aveva sussurrato scherzando:

-

In fin dei conti, sono come quegli scavezzacollo bacchettoni che saltano la

cavallina per anni e poi sono proprio quelli che esigono le ragazze più serie;

e si mostrano pure i più esigenti. - Avrà anche scherzato, ma diceva il vero.

La relazione intrecciata con Ada era la realizzazione più alta che avesse

raggiunto nel corso della propria vita. Nulla reggeva il confronto.

Incontrare

Ada, aveva significato ritornare a una concezione dell'amore completamente

diversa: a lui familiare, perché non molto lontana da quanto aveva udito dai

genitori, ma differente da quello che, da ribelle, aveva sperimentato lui fin

dall'adolescenza. Era vissuto tra gli adolescenti e i giovani dei tardi anni

'80, primi anni '90, abituatisi, in buona fede, a lasciarsi trascinare dalle

esperienze sentimentali e a non controllarle troppo, sicuri che andasse bene

così.

Ada

invece, apparteneva a un altro mondo: a quello delle brave ragazze e dei bravi

ragazzi che attendono ancora la prima notte di nozze per donarsi al proprio

amore. Con lei, lui aveva appreso il vero significato di un valore considerato

dai più ormai sorpassato, quasi un'anticaglia o un relitto per cui provare

fastidio: la purezza. Ada era sexy, secondo

lui tremendamente sexy: da lei

sprigionava una sensualità solare, nitida, degna delle più esuberanti giornate

estive in terra mediterranea. Lei era come lui si immaginava l'Italia: piena di

sole, di colori, di calore umano. Il suo cuore traboccava di passione, una

passione trascinante, dolce, eppure intensa, di quelle che alimentano non una,

bensì mille e una notte. Eppure, accanto a lei, si respirava aria di purezza.

Glielo aveva spiegato lei una volta, che cosa intendeva con quella parola:

-

Tanti pensano alla purezza in modo nevrotico, pieno di paura, come se

consistesse in una somma di divieti esterni e artificiali; e come se mantenerla

coincidesse coll'evitare delle macchie di sporco, alla maniera dei vestiti da

mettere in lavatrice. Ma la purezza è molto di più, straordinariamente di più

di qualcosa di tanto meschino. La purezza significa armonia, significa

soprattutto mancanza di egoismo; significa dedizione vera, significa rispetto.

Ecco: per la prima volta in tanti anni, con Ada John aveva conosciuto

sulla propria pelle la carezza lieve del rispetto, di un velo pudico che copre

delicatamente chi si ama, dell'estasi di essere amato per la persona che era.

Non c'era bisogno che lei glielo dicesse, perché ne era sicuro: non sarebbe mai

stata d'accordo a finire a letto con lui dopo un party. E non che lei non lo desiderasse: nessuna, il suo istinto di

uomo glielo suggeriva, lo aveva desiderato tanto quanto lei. Durante le loro

visite insieme, lo sguardo innamorato di lei scivolava sui lineamenti di lui

accarezzandoli dolcemente, scivolava lungo le sue larghe spalle, le braccia, il

torace e tutta la sua alta figura con il rapimento dolcissimo di chi contempla

una meraviglia e non se ne staccherebbe mai. Con lei John aveva compreso, nel

suo significato più profondo, il perché il suo contegno sarebbe stato tanto

diverso; se lei lo avesse conosciuto fuori, il vero, unico, grande motivo per

attendere la gioia suprema di una notte tra le sue braccia sarebbe stato uno

solo: l'amore per lui.

lunedì 23 maggio 2016

Kintsugi

Kintsugi

Kintsugi is the Japanese art of piecing together vases by a golden or silver thread: an art which shows a philosophical background too. The Japanese, in fact, appreciate a lot what is old, scarred, broken: it emanates the scent of deeper life. In this tale, which I sent to a literary competition on February, I connect kintsugi with the subject of ageing: this is particularly worthy of attention in our era, when we are often tempted to reduce everything, even weak human beings, to trash.

Biopsies, blood tests, chemotherapy, vomit; and then,

radiotherapy, hormones, nausea, bleeding; and again, bones aches, weakening muscles,

impaired sight, collapsing skin. And the solitude of days elapsing in a lonely,

pale, hospital room, staring at the ceiling; dejection, grey depression, even

despair, exploding suddenly in his heart; or the fear of ache, even more dreadful

than ache itself. All of this had become his daily routine since the day when

his specialist, with grey, watery eyes, had stared at him and spelled, in a

hardly audible voice:

- Carlo, it's prostate cancer. With metastasis in your

bones. You might have one year left, more or less.

Since then, he didn't recognize his existence anymore:

Carlo, riding a motorcycle and enjoying gymnastics and Nordic walking; Carlo steadily

frequenting movies, museums, the theater, libraries, and increasing his

collection of history books. He was 67, but still thirsty of life and youth:

and now he had almost forgotten how he was just two months before. Years long,

in spite of ageing, he had almost persuaded himself that he remained strong,

lively, young; and now, he had apparently lost all of his energy, his impassioned

zest for life. In the hospital, he lay on his bed, absent-mindedly, just

waiting for the next treatment and fit of nausea; at home, he unusually sat round-shouldered

in his wonderful, but now dusty, library, full of superb volumes. A relic among

relics.

And yet, in spite of this harassing depression,

sometimes he still felt a desperate craving for life: when he gazed at the

orange-reddish stripes of light expanding over the horizon, just minutes before

darkness fell definitively on the rocks of his Liguria, he longed for

wedging dozens of activities, one more frantic than the other, in those

ephemeral twelve months. But lately, he found no more strength for this. He

just lay inertly in his arm-chair. Feeling his face always more wrinkled.

Suddenly, he discovered himself lonely too. Since some

years he was divorced - an adventure with a pretty woman, two decades, perhaps,

younger than him, had resulted in the brutal collapse of his evanescent

marriage; a marriage looking like an empty shell since so much time that he

didn't remember when it had started to vanish. His wife had left and built

again a life of hers elsewhere, determinedly and aggressively as usual; and the

relationship with the younger lover, which had filled him with so much

enthusiasm and exuberance at first - well, it dissolved too. Now Edda, his

former wife, routinely visited him, with the achromatic solicitude of a

governess; as for his grand-children, almost teenagers (Francesco was hardly 15,

Martina 10), he had even less to share with them than with his own son, Enzo,

often away for work. When he tried to talk with them, they weren't impolite,

no, but distracted: their look wandered far away, outside of the window,

towards the light of the afternoon; and he felt unable to reach them and their lively

daydreaming. Unable to reach that light.

When he experienced some relief thanks to chemotherapy,

failing to piece together his schedule again, Carlo found some distraction just

on his sleepless nights, in scrolling websites on the Internet: websites

dedicated to his, maybe whilom interests - antiques, books, art. He had no time

anymore for books, they were too long to read: websites were more synthetic and

focused. He passed unnumbered, silent hours before the screen, unable to detach

his eyes from it: lest the night, now friendly, could suddenly clutch him with

a hostile grip. Sometimes he didn't understand what he read, but those exquisite

images - precious books, colorful ceramics, paintings blurred by the patina of

time - diverted his thoughts towards a more pleasurable reverie.

In a chat about restoration he had got acquainted with

a Japanese lady, Midori, an expert on kintsugi: the art of piecing together

broken vases by a thin thread of gold. She still lived in Nagasaki and, since

she was only 4, she was a survivor, a hibakusha,

of the nuclear explosion: not seldom, she shyly hint to the crushing

consequences of it, still lingering on her life like a poisonous cloud. But she

enormously loved her job, whose adepts were becoming increasingly rare: and by

email she explained techniques, showed him pictures of her tiny masterworks. She

had sent him a photo of herself too: a gentle, smiling lady, simply elegant in

her traditional kimono, with her hands joined as if she were born to bow.

A delicate friendship had developed; thanks to her,

Carlo discovered the beauty of Japanese poetry, so concise and striking: it

fitted more his urge to live.

And now, by night, many a time they shared their

worries. Her memory was weakening, because of an insidious form of Alzheimer:

and while he listed his ailments, depicting a life sliding imperceptibly toward

a dark tunnel, she grieved her memory.

- I'll forget, Carlo...And then?

- Strange. Sometimes I'd like to forget. Everything. -

He would have added: I'd like falling asleep and not awakening anymore.

- But if I forget, I won't be able to witness, above

all in front of young people, nor to forgive...The art of old age is

memory...and forgiving.

Her ideal of forgiving looked admirable to Carlo, and

he was aware that Midori went on to bear her testimony about the bomb in front

of class-rooms and a large audience, relating also her experience of forgiving,

shared by her Nagasaki Christian community. But the man considered forgiving

abstract, distant, like the moon: finally, he had a good American friend, Bill,

a typical, warm-hearted, cheerful inhabitant of the South, met during a stage

on finance: and, like many of his fellow-nationals, Bill felt no regret for the

atomic bombs. Nor any worry at all for any kind of Japanese forgiving. US had

done what was right for the world, full stop. In spite of his perplexity, Carlo

had never dared oppose the perspective of his friend, who, after all, was a

very nice man.

By the way, Carlo and Bill had heard from each other

just a few months before, and he was grieving his wife, Louise, who had

suddenly died of a heart attack after 38 years of marriage. Now he felt lost in

their large, pretty house on the banks of a wide river, and the sunset never

arrived for him sitting alone on the porch. He had started to cherish Louise's dainty

belongings and to preserve them like in a small, family museum. He didn't dare

leave the house anymore, even for a few hours.

Once, Carlo and Midori discussed about his library. He

was reluctant to leave it to his grandson Francesco: he showed no interest in

history, nor in books in general, and Carlo was afraid this wonderful

collection might go damaged or dispersed. He rather planned to leave it

to the local city library.

- Are you sure, Carlo? - Midori replied from the other

end of the world; a slight quivering could be guessed in her lines. - Are you

sure?

Just this reiterated question aroused his doubts, even

if her discretion did not dare advance beyond an invisible line. A week later,

Carlo made a try with his grandson:

- See? These books?...I might leave them to you.

Francesco raised his chubby, pinky cheeks towards him

with a flabbergasted look:

- Meeee???

- Yes. If you

want, all this can be yours. -

and, from his worn leather-chair, Carlo raised his hand in a circular, showing

gesture.

- Miiiine?!? Wow!!!

Francesco approached a shelf with the veneration of a

pilgrim in the cell of a sanctuary: and by a finger he caressed the colored

cover of a volume about World War I. It was the first one he asked to read:

maybe he was just attracted by the colors of the cover, but he tried. He was

discovering himself owner of an extraordinary treasure, a treasure he had too

long contemplated from a distance in awe.

This was a first spark in Carlo's now restricted sky:

pain and despondency were swallowing the rest. Midori went on to send him

detailed pictures of her restored vases, but he was not able to fully

appreciate those pieces of brown or grey pottery, encircled by golden threads,

sinuous like the tentacles of a silent spider. She tried to explain to him:

- It's our philosophy, wabi-sabi, which appreciates what's broken or worn. We don't throw away

what we have used for a long time: waste comes from failed relationships, even

with objects...Use makes them more precious, more perfect...

Among the pictures he also noted some expensive

artifacts, enveloped as well by those shining meshes.

- How can you accept that a costly piece of porcelain

goes broken? It will never be the same anymore, even if you repair it...

- No, it will become more precious. When we love

something, we feel compassion for it and accept it changing.

This reminded Carlo again of his friend Bill. After

Louise's death, he had religiously kept even the fragments of a precious, pearly

vase from Bavaria she had loved a lot. They were still stored in a drawer.

When, after a terrible week of bones-aches, he felt a little better, he phoned

to his friend in Georgia.

- Bill? Have you still those white pieces?

The shipping and restoration needed some weeks, so

much more so as Midori was now working always more slowly: but after two

months, an amazed Bill, opening a voluminous, brown package, marked with some

incomprehensible signs, discovered, amid a large amount of white paper and

styrofoam, a delicate, pearl-white piece of porcelain, embraced by an

embroidery of golden and silver lines. He had never got acquainted with any

Japanese: and he stared wide-eyed at the horizon, wondering how such beautiful

grace could inhabit those people that his father, while in the Pacific Sea, had

considered just as cruel enemies.

Bill's joyful exclamations and a sense of quiet

gratitude accompanied Carlo's weakening some days long, almost letting him

forget that his time was running out: and the little rest of it was always more

absorbed by the vapors of morphine. In the pauses among his excruciating

tortures, and dulling mist, sitting in his chair, he looked at Francesco, who

now frequently attended his library and shuttled almost whimsically from a book

to another: but Carlo enjoyed that sight. His grandson even witnessed some of

his chats with Midori. When he interfered, telling he had to do a school

research about World War the II, the gentle lady, who hid beneath her smile the

dread of losing always more fragments of her memory, agreed to recount her past

to him. Carlo listened, nodding quietly, while Francesco recorded Midori's

narrations on some MP3 files: oddly, she explained, she had never felt

compelled to capture her own voice on tape, because she had always believed in

the truth gushing from lively sounds. But could that stop, at least for a

little time, the inexorable dispersion of images and faces flowing away from

her mind like water from a broken piece of pottery? Who knows...

On a quiet summer sunset, spreading a golden drape on

Liguria rocky coasts, from the silence beyond the horizon Carlo, always more

tired, received a Japanese poem:

Ageing means forgiving:

forgiving leaves, as they fall down,

forgiving our body, as it collapses,

forgiving nature, as it abandons us,

forgiving others, as they forget us;

forgiving everything,

because it will go on to exist

also without us...

forgiving leaves, as they fall down,

forgiving our body, as it collapses,

forgiving nature, as it abandons us,

forgiving others, as they forget us;

forgiving everything,

because it will go on to exist

also without us...

He read her verses in silence. Fear, an unfathomable

fear of anything, still inhabited him, but now he cherished her vases: while

sinking in the dark tunnel at the extremity of his life, in that night of

senses, he could glimpse a delicate, golden web of loving gestures spreading among

continents and generations, thinly, delicately supporting him, in spite of fear

and pain, and piecing together the impossible...

Iscriviti a:

Post (Atom)